Cellar spiders, sometimes called daddy long-legs spiders, are common across the world; you may already recognize them because of their conspicuous habit of creating and hanging from a loose web, what you might call a cobweb, in that neglected corner of your room. By far the most common type is the one pictured here, whose name is Pholcus phalangioides.

How do you know the species in your house is this species?

Three main ways:

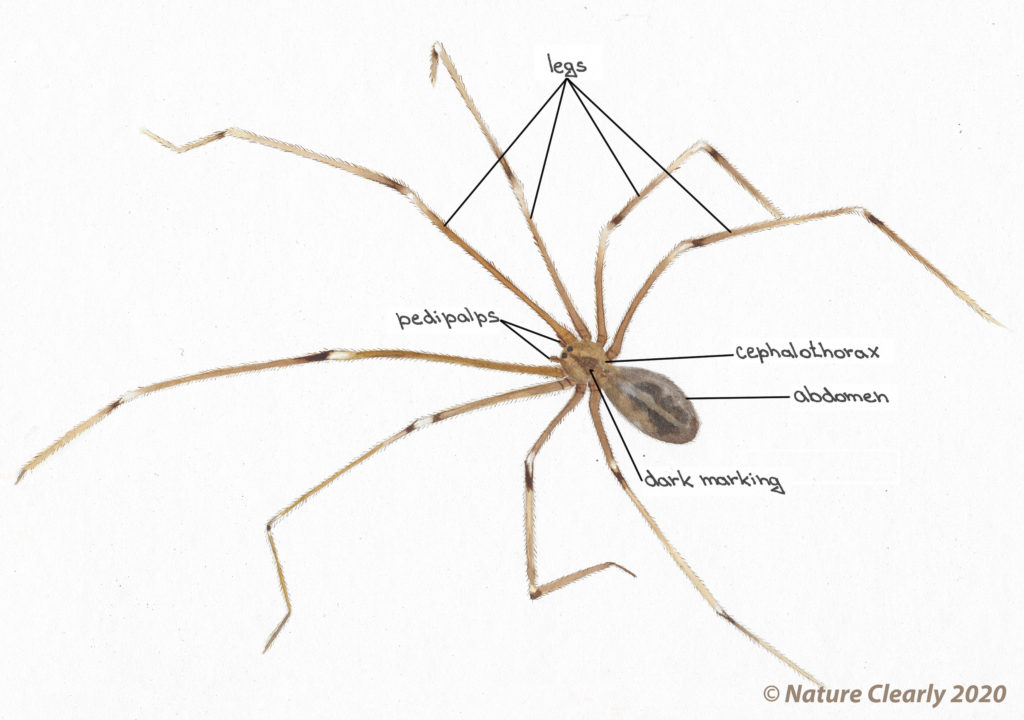

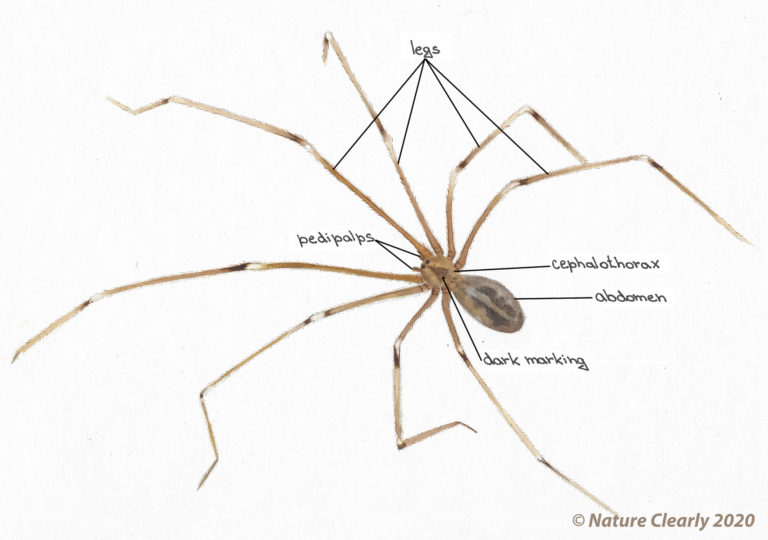

1) the extremely long legs, several times longer than the body

2) the abdomen (the hind part of the body, with no legs) is shaped like a long oval, not a sphere

3) the cephalothorax (cephalo = head; thorax = breastplate), the front part of the body with the legs, is light-colored, but has a dark oval or triangle marking in the middle of the back which is not distinctly divided into two halves.

The whole body, when fully grown and not including the legs, is about 1 cm long. Spiders that look just like this are found in buildings nearly everywhere in the world, and evidence about their distribution suggests that they were introduced from southern Europe to the rest of the world accidentally by the activities of human beings.

We know that many species that are close relatives of these spiders are found in caves and hollow trees in the wild, but there are a few, including Pholcus phalangioides, that we only find living in man-made structures.

Count the eggs before they hatch!

Occasionally you might notice something that appears to be a third, spherical body segment that has grown underneath the spider. This is not part of the body, but is an egg sac, a group of eggs that (in this species) the female lays and loosely binds with silk. You can easily see the individual eggs when you look closely—count how many you see! Also, while you are up close, notice how the egg sac is being held by the mother spider: she carries it using her chelicerae (singular: chelicera). Chelicerae are special types of jaws that spiders and their relatives have, which are normally used for feeding (each chelicera is tipped with a fang), but in this case the female is using these structures for a different purpose: holding on to her young.

If you’re lucky enough to see a spider with an egg sac in your own house, keep watching it every day–very soon those eggs will hatch! Look at the tiny spiderlings (baby spiders) that result. How many spiderlings do you count? How many legs do they have?

So if you see a Pholcus phalangioides without an egg sac, how do you know whether it’s a male or a female? Like most spiders, this can be very difficult if the individual is not fully grown, since they haven’t yet developed obvious differences. However, if it’s a large individual, look at the front of the body: there is a pair of short leg-like appendages called pedipalps. In the male, unlike the female, these end in boxing-glove-like structures.

Strange behavior

When disturbed, these leggy beasts often make a strange gyrating motion while in their web. You can stimulate them to do this quite easily: just poke a finger (use a pencil if you’re apprehensive!) into their web and they will begin vibrating wildly, sometimes for more than a minute. But why do they do it? This is a phrase we use often when speaking about insects and spiders: we don’t know why. Plausible ideas have been put forth, such as i) confusing potential predators of the spiders, or ii) that the motion caused by the web may help the spider tangle up an approaching insect. These sorts of behaviors are, in fact, incredibly difficult to conclusively explain. Think about how you might arrive at such knowledge: it would have to involve a huge number of observations under variable conditions, as well as some experimentation.

Should you get rid of cellar spiders?

If you can tolerate their presence, these sedentary spiders can actually be beneficial to have around as they can not only reduce the number of pesky flying and crawling insects, but can even prey on other, sometimes dangerous, spiders. They are known to engage in a very unusual behavior: they will wander a short distance from their own web and bait another spider into attacking them by mimicking the motions of a prey item, at which point they kill and eat the unsuspecting spider!

Do cellar spiders bite?

The venom of these spiders is no more toxic than that of an average spider (almost all spiders have venom glands!). These spiders, also like most others, do have fangs and in large individuals these are technically capable of piercing human skin. However, these spiders are not at all aggressive and bites are exceedingly rare and produce nothing more than a short-lived stinging sensation. We are happy to help dispel a pernicious myth: many people repeat the claim that these are the most venomous spiders in the world, but that their fangs are too small to bite humans. This is completely untrue.

If you don’t look very closely, you might confuse these spiders with another group of animals often called “daddy long-legs” or “granddaddy long-legs,” the harvestmen (order Opiliones). These have an oval body that looks like a single segment (not two segments as in spiders), and they have no fangs or venom glands. Unfortunately, the above myth often gets applied to them as well!